This is the 2nd half of an essay I wrote for an upper division Classics course at Ohio State University. With the scarcity of recent writing on this film, I wanted to give others a chance to stumble on it. Some minor edits were made to improve readability as I have excluded the first part of the essay.

The Siege of Sarajevo was a 1,425-day long siege that is among the most brutal attacks on a civilian population in recent memory. For background, there were three prominent ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina; Croats, Serbs, and Bosniaks. Ethnic tensions were at a breaking point. After the early 1990’s breakup of Yugoslavia, nationalism was at a peak. In a 1991 census, “44% of the population considered themselves Muslim (Bosniak), 32.5% Serb and 17% Croat, with 6% describing themselves as Yugoslav” (Klemencic 2004). The three ethnic groups each had a vision for their state’s future. An independence referendum was voted on completely by ethnic lines. As war began, Serbs fought to keep territories from claiming independence, and Croats and Bosniaks fought together against them. Eventually war broke out between Bosniaks and Croats as well.

The Serbs began an ethnic cleansing of Bosniaks, which Serbia and some others still deny to this day (several prominent Serb leaders – both Bosnian Serbs and Serbians – were found guilty of genocide in UN war tribunals). By April 1992, the rebel Serbs controlled 70% of the country and began shelling the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo (Carroll 2009). This war torn city has become of the most identifiable parts of the Bosnian War.

Though it may be only a few paragraphs in history textbooks on our side of the Atlantic, it was a total-war hellscape in Bosnia. In September 1992 (in the 5th month of the siege which would last 41 months more), William Pfaff wrote;

“They will not be conquered because a large modern industrial city of 350,000 people cannot be taken other than by a street-by-street infantry and tank assault, which is entirely beyond the abilities of the Serb militia. The actual resistance of Sarajevo`s people consists mainly of getting up each morning, going to whatever work they are doing, doing it, carrying on, finding something to eat, avoiding the snipers, and sleeping fitfully through the nighttime bombardments.” (Pfaff 1992)

Serb forces fired an average of 300 shells per day into the city. Snipers were described as shooting “anything that moved”. This ‘anything’ very much included children. Thousands died in the siege, many (although not all) by the tactical, calculated bullets of snipers.

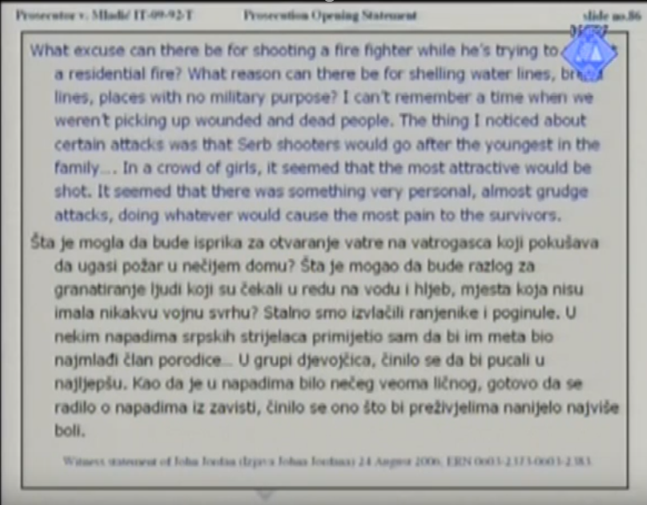

Various accounts of their actions were brought up in UN war tribunals, however I did not find any information on snipers being indicted for war crimes. In a quest to avoid biased sources (and regarding the Bosnian War, there is no shortage of these), I found YouTube footage from a 2012 UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) prosecution, where prosecutor Dermot Groome lays out a case against former Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic. I realize that a prosecutor is, by nature, a biased party, but I am drawn to the legitimacy of the UN. Here, he described the sniper fire:

“Mladic’s use of snipers in the context of the attack on the civilian population was not at all like the use of snipers in armed conflict. It was a strategy of shooting civilians from a hiding spot, giving them no warning or reasonable prospect of taking cover. It was about creating insecurity, about creating terror.” (ICTY 2012)

Groome also presents the observations of a volunteer firefighter in Sarajevo:

“The thing I noticed about certain attacks was that Serb shooters would go after the youngest in the family… in a crowd of girls, it seems the most attractive would be shot. It seems there was something very personal, almost grudge attacks, doing whatever would cause the most pain to survivors.” (ICTY 2012)

All in all, I have probably spent enough time delving into the horrors of the Siege of Sarajevo for the purposes of this essay. In short – it was Hell.

Knowing what we do about the Siege, it makes sense now that a foggy day was such a special occasion for Sarajevans in the final scenes of Ulysses’ Gaze. Under the blanket of fog, the civilians were shrouded from sniper fire. I found this quote[1] from the archive curator, Ivo Levy, especially powerful:

“Footsteps and voices? […] the fog… I sensed it. In this city, the fog is man’s best friend. Does it sound strange? It’s because it’s the only time the city gets back to normal. Almost like it used to be. The snipers have zero visibility. Foggy days are festive days here, so let’s celebrate!”

The curator hears music in the background, and excitedly says;

“Music… oh yes. A youth orchestra… Serbs, Croats, [Bosniak] Muslims… they come out when there is a ceasefire. They go from place to place and make music in the city. How about it, shall we go out too?”

After spending several paragraphs above discussing the atrocities of the Siege, this scene is especially meaningful. In a bloody, genocidal war, this youth orchestra is symbolic and idealistic, representing a group of the three ethnic groups coming together in the time of peace. It represents how things could be, or maybe how they used to be.

A arrives at Sarajevo after escaping Calypso’s island, notably wearing another man’s clothes. However, A’s time in Sarajevo does not end as happily as Odysseus’ journey ended in Ithaca. As he and Levy enjoy the foggy day in Sarajevo, they run into Naomi, the daughter of Levy (played by Morgenstern, the same actress who plays essentially every woman A interacts with). They dance, as she likely represents a Penelope figure. Naomi, A, and Levy begin to walk down the river, but a car of soldiers rolls up off-screen. Levy tells A to stay back as he follows his daughter to investigate. Following a Classical Greek tradition of off-screen deaths, Levy and his daughter are gunned down by soldiers behind the wall of fog. A finds their bodies and wails in a long shot where the camera backs away just enough for him to be completely obscured by the fog.

In a great stroke of luck, I was able to find a PDF [2] of ‘Interviews’, 195 pages of combined Theo Angelopolous interviews translated and published as a book. Here, I found the transcript of an Israeli radio show where Angelopolous described his fascination with Saravejo:

“My Interest in politics and the Balkans is very easy to explain. Look at the history of this century and you will notice that its first momentous event took place in Sarajevo, and now, as we approach the end of the century, we are again in Sarajevo. This proves to what extent we have all failed. Living in the Balkans, I am naturally much closer to the events, and much more concerned than the rest of Europe. I wanted to shoot in Sarajevo, but couldn’t. Everything was lined up for us to go there. We were all ready to go, waiting for our plane in Ancona, when the plane that left before us was turned back because the bombing had started again.” (Interviews 2001)

The 20th century history of Bosnia began and ended with tragedies in Sarajevo. To some degree, the entire 20th century history of Europe is bookended by these tragedies. In 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo (Backhouse 2018). At the time of the film’s release in 1995, Sarajevo was in the midst of its siege.

This argument about the cyclical nature of the film originally came from Marinos Pourgouris, a Greek academic, and his chapter in “Mythistory and Narratives of the Nation in the Balkans”. The famous journey of Odysseus had a beginning and an end in Ithaca, and his return brings a sense of order back to Ithaca. In Ulysses’ Gaze, references are made to the cyclical nature of A’s journey. In the beginning of the film, as he has returned to Greece from America, he states, “my end is my beginning”. [3]

Closing:

This film is far from a typical Hollywood film, the typical type of film I engage with. Angelopolous himself has expressed a great deal of disdain for where film is heading and how Hollywood has changed cinema in Greece:

“We know that European cinema is not doing very well lately; less tickets are sold. The theatres today are no longer that privileged place of encounter between the creative artist and his audience. There is a small elitist minority still looking for that encounter, but the vast majority is favoring the American movies, which, as far as I am concerned, are not films but just images printed on celluloid.”

As I discussed on page 2 (note – this refers to part of the essay that I did not upload), the reviews for this film were highly polarized. Considering the raving endorsements and scathing critiques of Ulysses’ Gaze, I think this film is a great example of how a film can be received in such profoundly different ways based on the lived experiences of different people. Long spans of it still don’t make sense to me, but having learned more about the history of the region, I can appreciate the depth of the film. As someone who generally doesn’t understand deep, symbolic art and film, it was very exciting to take a deep dive into some of this film’s scenes as they related to Balkan history and Homer’s Odyssey.

A Few Random Angelopolous Quotes (curated by

“In any case, Greeks are a nation of emigrants. At the turn of the century, half of them went to America. There are one and a half million Greeks in the U.S. There are already 300,000 in Germany. They are everywhere, and instead of contributing to Greek economy at home, they are working for others. The Americans are coming into Greece now, claiming they wish to industrialize the country, but of course they will do it only if it is profitable for them. And Greece, for many, is now the fifty-first state of the Union.”

Question: You are implying Greece is a Third World country.

Angelopolous: That is the way things are. The Third World is not limited to Africa and Latin America. If you ask me, it includes Greece and Turkey too. We do not belong to the West, we are not part of Eastern Europe-we live at the crossroads of modern civilization. However, we happen to occupy a strategic point in the Middle East; therefore, we are important to American politics. Had it not been the case, their attitude towards us would have been completely different.

Q: You mentioned that Ulysses’ Gaze is, among other things, a love story. But is it really about love or the impossibility of loving? At one point, your protagonist says, “I am crying because I cannot love you.”

A : That phrase is taken from Homer’s Odyssey. Ulysses remained seven years on Calypso’s island, but he would often go down to the sea and cry. For he could not love Calypso; he was always thinking of Penelope. He wanted to love her, but couldn’t. As a matter of fact, at the end of my film, the hero meets once again his first love. It’s a film about firsts-first love, first look, the initial emotions that will always be the most important in one’s life.

Footnotes:

[1]: timestamp 2:24:27 in this YouTube version of the film (all timestamps in this essay refer to this video)

[2]: Available from Amazon here – https://www.amazon.com/dp/1578062160

[3]: timestamp 13:08

References:

Andersen, Odd. A Young Boy Plays 22 April 1996 on a Tank. April 22, 1996. Accessed December 5, 2018. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/young-boy-plays-22-april1996-on-a-tank-in-the-sarajevo-news-photo/134244637.

Getty Images states “Photo credit should read ODD ANDERSEN/AFP/Getty Images”

Angelopoulos, Theo. Greece, 1997. Accessed November 29, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hO3b-bHmu1Q.

(Ulysses’ Gaze available on YouTube here)

Alberó, Pere. “A Gaze by Ulysses towards the Balkans.” Quaderns De La Mediterrània 23 (2016): 115-23. Accessed November 27, 2018. https://www.iemed.org/observatori/arees-danalisi/arxius-adjunts/quaderns-de-la-mediterrania/qm23/A Gaze by Ulysses towards the Balkans_Pere_Albero_QM23.pdf.

Chouinard, Alain. “Historical Argument, Involuntary Memory, and the Subversion of Balkanist Discourse within Theo Angelopoulos’ Ulysses’ Gaze.” OffScreen. February 2016. Accessed November 28, 2018. https://offscreen.com/view/balkanist-discourse-ulysses-gaze#fn-5-a.

Carroll, Chris. “Serbs Face the Future.” National Geographic. July 2009. Accessed December 05, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2009/07/serbs/.

Ebert, Roger. “Ulysses’ Gaze Movie Review & Film Summary (1997).” RogerEbert.com. April 18, 1997. Accessed November 27, 2018. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ulysses-gaze-1997.

Fainaru, Dan, ed. Theo Angelopoulos : Interviews. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Howe, Desson. “Ulysses’ Gaze.” The Washington Post. September 16, 1997. Accessed November 27, 2018. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/ulyssesgaze.htm?noredirect=on.

Klemencic, Matjaz, Matjaž Klemenčič, and Mitja Žagar. The former Yugoslavia’s diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. Abc-clio, 2004.

Pfaff, William. “LIFE, DEATH AND SURREALISM IN THE HELL THAT IS SARAJEVO.” Chicago Tribune. September 27, 1992. Accessed December 09, 2018. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1992-09-27-9203280117-story.html.

Pourgouris, Marinos. Mythistory and Narratives of the Nation in the Balkans. Edited by Tatjana Aleksić. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007.

Chapter 9 covers Ulysses’ Gaze

“Prosecution Opening Statements – Mladić (Part 5/5) – 16 May 2012.” YouTube, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), 18 May 2012, youtu.be/rQ2SfiPJ-cI.

Stratton, David. “Ulysses’ Gaze Review.” SBS News. December 31, 2008. Accessed November 28, 2018. https://www.sbs.com.au/movies/review/ulysses-gaze-review.

[1] timestamp 2:24:27 in this YouTube version of the film (all timestamps in this essay refer to this video)

[2] A PDF obtained in a perfectly legally manner, certainly not from a virus-ridden Russian website

[3] Timestamp 13:08